The virus and the storm

Cyclone Harold brings new meaning to the concept of remote working in the Pacific Islands

By Elizabeth Millership

Families crammed together into evacuation centres as 270 km/h winds roared outside. Neighbours stood in tightly knit groups watching as their homes and livelihoods were washed away. People across the islands desperately tried to call loved ones, face masks dangling from wrists, temporarily forgotten.

In early April, across the island nation of Vanuatu, Cyclone Harold laid bare what happens when a natural hazard crosses the path of a global pandemic.

Vanuatu — whose remoteness has so far protected it from COVID-19 — is now dealing with widespread devastation left by the second strongest storm to ever hit the country. At the same time, movement restrictions and strict quarantine measures add an unprecedented layer of complexity to the humanitarian response.

Over 700 miles away across the Pacific Ocean, the quarantined streets of Fiji’s capital, Suva, are eerily quiet. It’s a stark contrast to the frenzied ping of emails, messages and calls inside the home of Hlekiwe Kachali, who has coordinated the activities of the WFP-led Emergency Telecommunications Cluster (ETC) in the Pacific for the past two years.

“We are locked down in Fiji,” she explains. “When Cyclone Harold hit Vanuatu and then Fiji in early April, we could not deploy from Suva because all the borders were closed…I would have deployed to get to Vanuatu on a boat, a plane, a flying jet — anything! In this case, we are coordinating the telecommunications response using what is already on the ground,” Hlekiwe says over an unstable line from Suva.

WFP and the ETC operate as part of the Pacific Humanitarian Team, a network of organizations assisting Pacific Island countries to prepare for and respond to disaster. In the wake of Cyclone Harold, these partnerships have been essential to unlocking the response.

National disaster management offices, local government, partners, broadcast companies and regulators are the arms, eyes and ears of the ETC’s response to Cyclone Harold. With roots stretching back years, these relationships showcase preparedness in action.

Daily, Hlekiwe can be found pacing the floor of her apartment immersed in calls with local partners: “We draw up solutions while on the phone, asking ourselves what will work that does not rely on deployment. We are striving for good solutions that work now, with what we have,” she says emphatically.

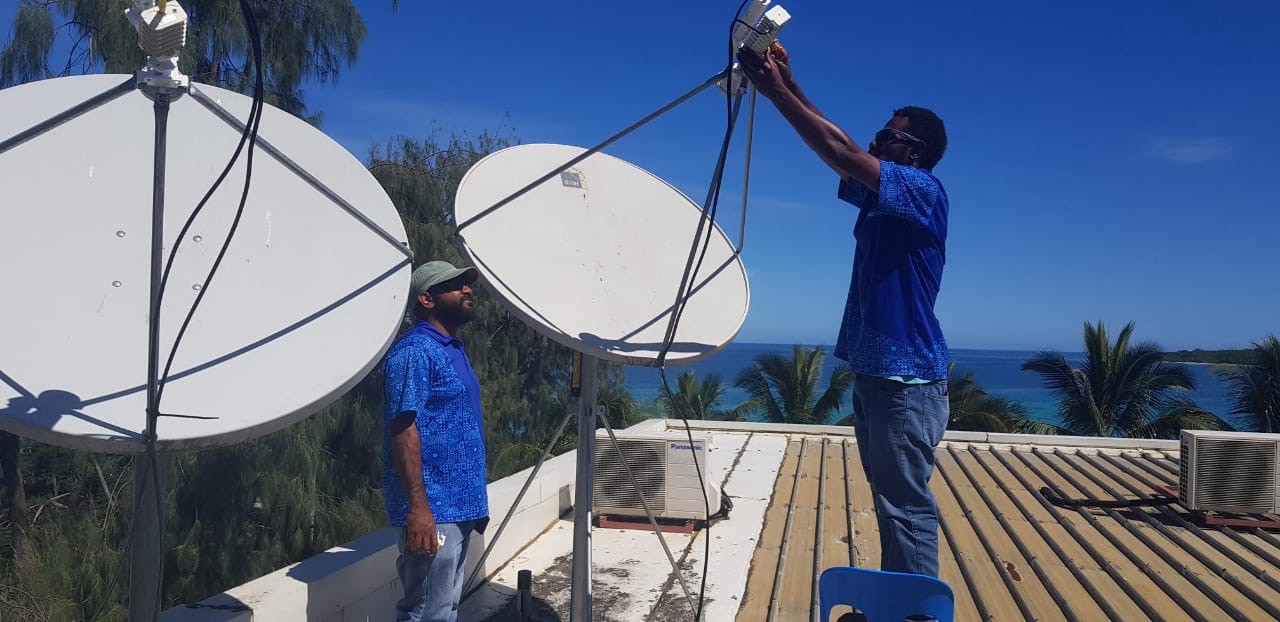

One of these solutions has been found in the Crisis Connectivity Charter, an ETC-led agreement which accelerates access to satellite-based communications when local communication networks are affected by disaster.

In its first activation of 2020, Inmarsat and Intelsat — two of the Charter’s signatories — have committed satellite capacity on the ground to reconnect humanitarians and communities unable to use the collapsed networks of Vanuatu and Fiji. Regional satellite experts Wantok Vanuatu, Gilat Australia and Av-Comm have all stepped in to assist the Charter’s signatories.

Inmarsat is providing mobile Internet access and communications to help coordinate the response and support assessment missions to Fiji’s Kadavu and Southern Lau islands, both devastated by Cyclone Harold.

Inmarsat’s Mike Carter knows how critical communications can be in the aftermath of a disaster: “Delivering assistance to populations attempting to lockdown in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic makes this even more of a challenge. Access to up-to-date information on the ground is more important than ever,” he says.

The Charter’s Coordinator, Pedro Molinero, explains: “Because of the limitation of movement of flights and personnel, the Charter is in close contact with the ETC to identify and reuse equipment already deployed in the field to cope with the response to Cyclone Harold.”

“In these exceptional days, satellite telecommunications are — more than ever — a key element in keeping our communities together, informed and protected against isolation,” Pedro says.

Intelsat has been integral to the response in Vanuatu. “We’ve had to get creative in this response and pull together a solution from multiple organizations,” says Intelsat’s Colleen Parent. “The response to our request for help was overwhelming!”

Comparing the connectivity solution for Vanuatu to completing a puzzle, Colleen points out, “Any effective disaster recovery solution requires advanced planning and robust processes which can be activated at a moment’s notice. When those plans cannot be used, having an open platform with multiple ways to support gave us the flexibility to respond to the call for help.”

Underlining how essential communication is — and how agile the ETC has needed to be — the Cluster has also been a key support to the World Health Organization’s Pacific Joint Incident Management Team since early March in its response to COVID-19.

The team is preparing 22 different Pacific Island countries and territories to prevent the spread of the virus, from healthcare and communication perspectives. As Hlekiwe puts it: “we are dealing with responses in the same places, but which call for very different skills. At specific points in each response, we are calculating and coordinating two sets of equipment and even two different sets of partners.”

“You can so clearly see the devastation wrought by Cyclone Harold in Vanuatu and Fiji. When it comes to the pandemic, we’re responding to something far more intangible,” she says.

Another in a series of phone calls lights up Hlekiwe’s phone. This time it’s Intelsat on the line, ready to coordinate its connectivity solution.

One aspect of this two-fold emergency has become increasingly visible: the foundation of reliable partnerships on which the Pacific emergency telecommunications response has been built.