Risk is real, and rising

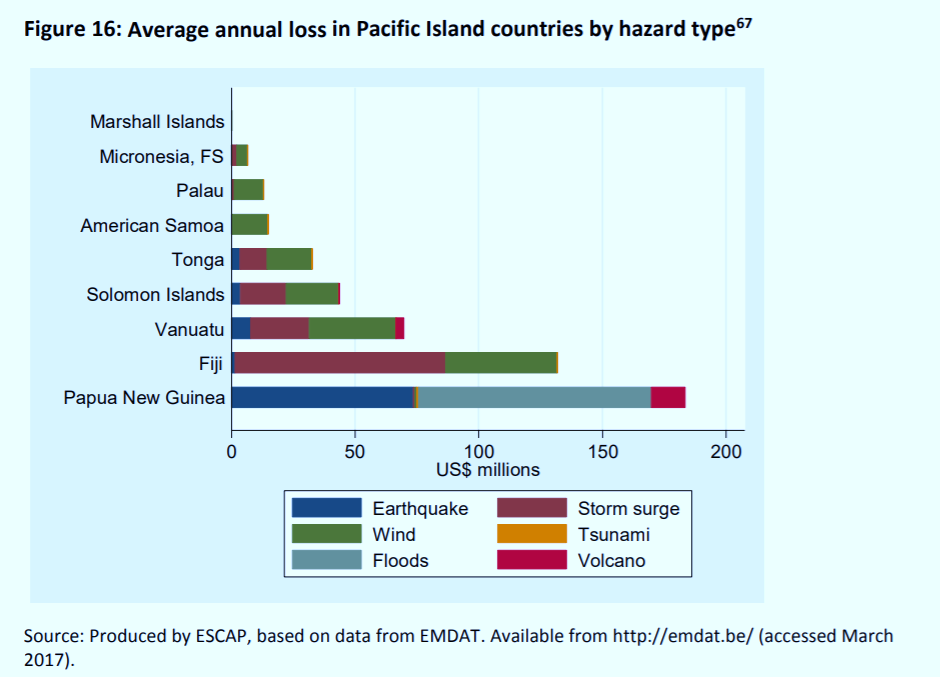

While the vulnerability of Pacific Islands varies according to situational factors, they all have something in common: high exposure to a host of hydrometeorological and geological hazards like cyclones, tsunamis and earthquakes.

The facts are sobering. From 1950 to 2011, extreme weather-related events in the Pacific Island Countries (PICs) affected around 9.2 million people, caused 10,000 deaths, and damage of around USD 3.2 billion.[1]

Climate and disaster risk compound the vulnerability of highly exposed Pacific Islands. Climate change threatens the very survival of some of these countries. We know that climate change exacerbates the strength and ups the frequency of natural hazards, which can result in life-changing disasters – leaving death and destruction in their wake. We also know there is a link between climate change and socio-economic systems: sudden and longer-term progressive damage to the natural environment has an equally immutable impact on communities – especially those reliant on the natural environment for livelihoods and subsistence.

From a development standpoint, when adverse impacts are felt at the community-level, this translates into problems at the national – or macro – level. Average annual loss (AAL) is used to understand this damage, in terms of gross domestic product (GDP). In simpler terms, AAL is the expected loss per year, averaged over many years.

Tropical Cyclone Winston is a good example. This Category 5 cyclone struck Fiji in 2016, wiping out 31% of the country’s GDP, estimated at USD 1.38 billion.[2] The situation was even more dismal in the case of the Kingdom of Tonga, with Tropical Cyclone Gita (2018) decimating 37.8% of its GDP. [3]

[1] World Bank (2016). Pacific Possible: Climate and Disaster Resilience.

[2] Government of Fiji (2016). Post Disaster Needs Assessment: Tropical Cyclone Winston.

[3] Government of Tonga (2018). Post Disaster Rapid Assessment: Tropical Cyclone Gita.